Gazza on my mind this week. No real reason. A home tie to take us to Wembley, can’t complain about the semi-final draw and Liverpool’s ability to find a banana skin more often than Charlie Chaplin have all contributed to a sense of ease and relaxation. So the mind wanders back to past glories, and in modern times there are few more glorious than Paul Gascoigne. And as is the way with these things, I’ve not been looking but Gazza has found me, with a great story from Daveyboy in the comments section of my last article, Morris Keston gives him a mention on twitter and then there he is in the book I’m reading.

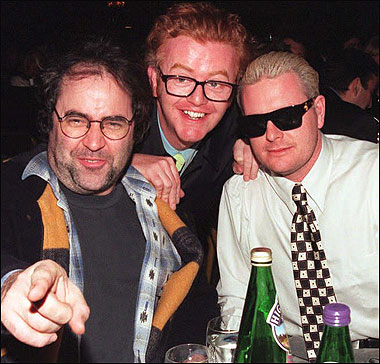

A Man Who Looks Like Danny Baker. From the Site http://menwholooklikedannybaker.com. You Couldn't Make It Up

I’ve been a big fan of Danny Baker for many years. Not quite in the league of Kennedy’s assassination or Princess Di’s death but I vividly recall the first time I heard his radio show. On a bleary eyed Saturday morning, making breakfast for the kids, wife at work and no chance of football, the mindless banality of Capital Radio would provide scant diversion from the drudgery of breakfast and the washing up, but it was the best I could come up with. Turning the dial, Robert Cray’s upbeat blues ‘Smoking Gun’ ripped from the radio and I hung around to see who on earth was playing this stuff. From then I’ve followed the fabulous Baker boy around the airwaves. Many times I’ve had to pull over because I’ve been laughing so much but his sense of the absurd and relaxed freeflowing presentation masks an effortless mastery of the medium of radio. Now he’s back at 606, a show he originated and was then dismissed from because he not entirely seriously suggested that aggrieved fans may wish to beat a path to the door of a certain referee. In reality this was the excuse because it was clear his face didn’t fit – on 606 he wanted to talk about things other than Fergie’s latest press conference or whether that was a penalty after 37 replays. Like things you had confiscated at the turnstiles or unusual places to play football.

His knockabout style and apparent lack of a coherent career plan (at BBC London he works on a handshake rather than a contract) hides his status as an insightful and shrewd observer of popular culture, especially football and pop music. His 2 hours on BBC London on the day after Michael Jackson’s death, where without a script he reminiscenced around his time in LA before, during and after his NME interview with Jackson back in the 80s, the last major independent interview with him, was touching, funny and honest, and said more about Jackson than the sum of all the tosh that overwhelmed the media for weeks after.

His latest book Baker and Kelly – Classic Football Debates, written with Paxton Road stalwart Danny Kelly, was certain to find its way into my Christmas stocking. Someone would put two and two together as they wandered round the bookshop ten minutes before closing on December 24th, when Waterstones is jam packed with desperate punters scooping up any offering that possessed a connection with loved ones for whom they could not think of anything that they would really want. It’s a bit like the aunt who every year gives you the latest Westlife album, because one Saturday round at hers, squirming with embarrassment at Celebrity Idol Factor on Ice, your morale squashed as flat as a Kraft cheese slice run over by a steamroller, you thought it would keep everyone happy by saying that parts of the chorus were ‘quite nice’. Quite nice. How inoffensive and non-committal is that. It implies that your nervous system was closed down totally save for a pulse sufficient to lift one eyelash a fraction of a millimetre. But to your aunt, it indicates undying appreciation of their irish might, to be rewarded each and every Christmas with their latest offering.

The only question with the Baker and Kelly book was not if I would receive one but how many. In the event, it was only a single copy (but four THFC 2010 calendars….). It’s a largely disappointing effort, an erratic mix of funny anecdotes, rehashed phone-in material that does not translate well to the page and fillers, all of which stinks of money for old rope. Even the print is spread wide apart so as to reach the end of the 300 pages without undue effort. But there are several gems, one of which is an eye-witness account of Gazza’s infamous spree in London. Stuck in traffic, Gazza cannot sit still so he jumps out the cab and commandeers a London bus, complete with passengers, which he then drives round the Marble Arch roundabout. Leaping out, he spots some workmen and while he cadges a fag, digs a hole in the road with a pneumatic drill. Baker and friend Chris Evans look on as he reaches their destination, a media awards ceremony to which he had not been invited, via a Bentley that he flagged down at the lights – the elderly couple in the back were only too glad to help. This was front page news at the time, with Gazza and his drinking pals both celebrated and simultaneously castigated by the tabloids in the ways that only they know.

Baker maintains that they were not drunk but the redtops were determined to imply otherwise. The bottles in the photo (not from the book) are water but that’s

not the story that the tabs want. But the most touching element of this story is the public’s reaction to Gazza – everybody loved him. People from different backgrounds felt good just to see him. They cheered him wherever he went, went along with his fun (and it was all fun to him) and he made them feel better. Everyone felt they knew him, sharing jokes, shouting hallo, wishing him well. For his part, he could talk to anyone and stopped to give them all the time of day. No PR, no manufactured celebrity status, just Gazza.

Gascoigne was loved by the people, genuinely and unashamedly so, in a manner that may never be repeated. Pre-Sky, this was a time when players were not so tainted by their riches as they are now, separated and aloof from their fans. If Rooney wins us the World Cup, he would not be able to set foot outside the front door without a phalanx of bodyguards and PR people, and the sad thing is, he may not wish to.

Baker’s affectionate tribute to his friend opens our eyes to one side of his personality but obscures another, the demons that have driven him to the bottom of the deepest abyss. He touches upon the reasons driving Gascoigne on, his restlessness, the need to fight off a boredom that would engulf him when, finally, there were no more highs to sustain him: “The brighter his star shone the more its inevitable collapse into a black hole haunted him.”

It’s a powerful image of impending doom touching even the most exciting crazy moments but it does not look the real problem in the face: Paul Gascoigne suffers from a serious mental health problem. This is not criticism of the man, how can it be, it’s an illness, nor does it belittle any of his achievements on the pitch. If anything it makes them even more miraculous, given that they were performed under such duress. Gascoigne according to his autobiography was a restless, distracted and hyperactive child whose obsessive behaviour was under control but manifested itself later in life as the pressure eroded his coping mechanisms. He saw a therapist of some sort once as a child but never returned. Baker remarks on how Gazza was constantly talking and narrating his day, reminding himself of what was happening to him as a means of calming himself down.

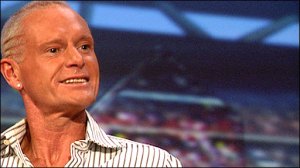

Later, when football no longer sustained him, the drinking, depression and self-abuse took hold. The week long drinking binges by messrs Baker, Evans and Gascoigne are a myth, says Danny, and the London escapade ended with Gazza on Baker’s sofa, chatting with the family as they watched TV. However, he was supposed to be in his log cabin in the remote Scottish hills, which was the bolt hole and place of safety that his manager at the time, Walter Smith, had sorted out. Now we see a pallid and broken man, going through the motions and blank behind the eyes, struggling to rehabilitate himself.

Danny Baker has written an eloquent and insightful piece about the Gazza he knows, which says so much about the man and yet skirts round the one unmentionable in modern football. Sex, alcohol, drugs and infidelity are all open to debate, but one subject remains taboo: mental health. We can’t talk about it. The man suffers, yet he’s given offers to manage a football team or to get back into coaching, or to be a TV celebrity. I heard a rumour that he was going into Celebrity Big Brother and I swear I would have chucked in my job and set up a protest camp outside the studios. We fear mental health problems but they are just that, health problems. Let’s have some honesty about the pressures of modern football and talk more openly about their effect on vulnerable people. Show compassion to sufferers and offer sympathy and treatment. Above all, give them realism – don’t ask too much. The people around Gazza need to look after him. Gazza made us happy, now let’s care for him. A true Tottenham great, we owe him.

Add to: Facebook | Digg | Del.icio.us | Stumbleupon | Reddit | Blinklist | Twitter | Technorati | Furl | Newsvine